When the Bronze Age world collapsed around 1177 BC, most civilizations crumbled. Yet along the Levantine coast, a remarkable transformation occurred. The Phoenicians not only survived the catastrophe but emerged as the Mediterranean’s dominant commercial power for nearly a millennium. Eric H. Cline’s “After 1177 B.C.: The Survival of Civilizations” reveals how Phoenician maritime innovation, commercial networks, and cultural adaptability turned potential extinction into unprecedented success.

From Territorial States to Maritime Empire

Before the Bronze Age Collapse, the Levantine coast was home to prosperous city-kingdoms operating within the broader Eastern Mediterranean trade network. Cities like Byblos, Tyre, and Sidon engaged in commerce but remained primarily territorial powers focused on controlling land and agricultural resources. The collapse of surrounding empires and the disruption of established trade routes threatened their existence.

What distinguished the Phoenicians was their willingness to fundamentally transform their societal model. Rather than attempting to rebuild territorial kingdoms like those that disappeared, they pivoted toward maritime commerce and colonial expansion. This wasn’t merely adaptation—it was radical transformation. The Phoenicians recognized that the old world was gone and new opportunities existed for societies willing to embrace change.

Archaeological evidence from Phoenician cities shows this transformation unfolding during the twelfth and eleventh centuries BC. While many Eastern Mediterranean sites show abandonment or severe decline during this period, Phoenician coastal cities maintained continuity. They reorganized their economies around shipbuilding, navigation, and long-distance trade rather than agricultural production and territorial control.

The Power of Commercial Networks

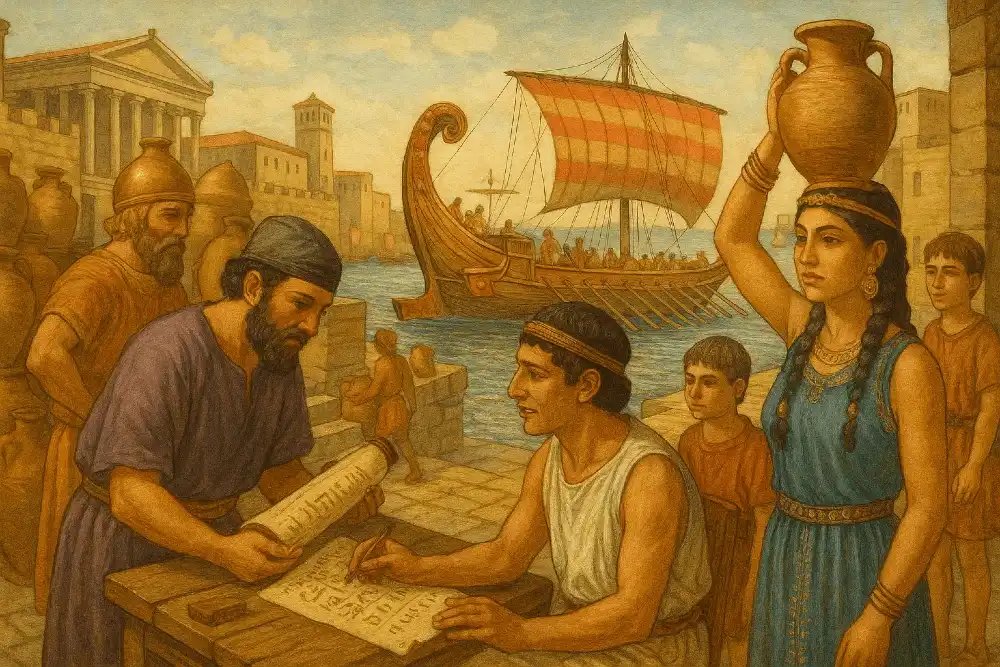

Phoenician success rested on developing commercial networks that spanned the known world. Unlike Bronze Age trade that relied on palace bureaucracies and diplomatic relationships between kingdoms, Phoenician commerce operated through independent merchants and city-state networks. This decentralized structure proved remarkably resilient, as it didn’t depend on any single political entity’s survival.

Cline’s research in “After 1177 B.C.” highlights how Phoenician merchants established trading posts and colonies throughout the Mediterranean. From Cyprus in the east to Spain in the west, Phoenician commercial influence extended farther than any Bronze Age empire. They traded in diverse commodities including timber from Lebanon’s famous cedars, purple dye from murex shells, metalwork, glassware, and finished goods from across the ancient world.

The Phoenician approach to commerce emphasized partnerships rather than conquest. Unlike empires that imposed control through military force, Phoenicians established mutually beneficial trading relationships. This strategy proved more sustainable than military expansion, as it created stakeholders in Phoenician success rather than resentful subjects. Their commercial networks became increasingly essential to economies throughout the Mediterranean, giving Phoenicians economic influence without the costs of maintaining territorial control.

Maritime Technology and Innovation

Phoenician maritime superiority wasn’t accidental—it resulted from continuous technological innovation and accumulated expertise. They developed advanced shipbuilding techniques that produced vessels capable of long-distance voyages across open seas. Phoenician ships were among the most sophisticated of their era, combining cargo capacity with navigational capability.

Navigation knowledge gave Phoenicians significant advantages. They mastered celestial navigation, allowing voyages beyond sight of land. They compiled detailed knowledge of winds, currents, and seasonal weather patterns across the Mediterranean. This expertise became proprietary information that Phoenician merchants guarded carefully, maintaining competitive advantages over potential rivals.

Phoenician innovation extended beyond ships to include commercial practices and organizational methods. They developed standardized weights and measures that facilitated trade. They created accounting systems for tracking complex multi-party transactions. They established credit arrangements that enabled commerce across vast distances and time periods. These innovations made Phoenician merchants valuable partners throughout the ancient world.

The Alphabet: Cultural Innovation with Global Impact

Perhaps the Phoenicians’ most enduring contribution was alphabetic writing. Before the Phoenician alphabet, writing systems used complex pictographic or syllabic scripts that required extensive training to master. Egyptian hieroglyphics involved hundreds of symbols. Mesopotamian cuneiform was similarly complex. These writing systems remained specialized skills controlled by scribal elites.

The Phoenician alphabet simplified writing dramatically. Using approximately twenty-two consonant symbols, it could represent spoken language efficiently and could be learned relatively quickly. This innovation democratized literacy, making written communication accessible beyond specialized scribes. The alphabet’s simplicity and effectiveness ensured its rapid adoption across the Mediterranean world.

Cline emphasizes how alphabetic writing supported Phoenician commercial success. Merchants could keep records, communicate with distant partners, and manage complex transactions without requiring palace bureaucracies. The alphabet enabled decentralized commercial networks that wouldn’t have been possible with more complex writing systems. This practical innovation became one of humanity’s most important technological advances, eventually evolving into Greek, Latin, and ultimately modern alphabets used worldwide.

Colonial Expansion and Cultural Adaptation

Phoenician colonies represented another key element of their success strategy. Beginning in the ninth century BC, Phoenicians established settlements throughout the Mediterranean, from Cyprus to North Africa, Sicily, Sardinia, and the Iberian Peninsula. The most famous Phoenician colony, Carthage in modern Tunisia, eventually became a major power rivaling Rome.

These colonies weren’t merely trading posts but substantial settlements with their own populations, economies, and political structures. Phoenicians demonstrated remarkable cultural adaptability in their colonial ventures. Rather than imposing uniform cultural practices, they adopted local customs and integrated with indigenous populations while maintaining core Phoenician identity and commercial connections.

Archaeological excavations at Phoenician colonial sites reveal this cultural flexibility. Phoenician settlers incorporated local architectural styles, adopted regional deities alongside their own gods, and intermarried with local populations. This adaptability contrasts with later colonial ventures by Greeks and Romans that often imposed metropolitan culture on colonies. Phoenician willingness to adapt made their settlements more sustainable and integrated into local contexts.

City-State System and Political Organization

The Phoenician political system contributed to their resilience and success. Rather than unifying under a single empire, Phoenicians maintained independent city-states that cooperated through commercial and cultural networks. Major cities like Tyre, Sidon, and Byblos competed economically while sharing broader Phoenician identity and interests.

This decentralized political structure provided significant advantages. When one city faced challenges, others could continue functioning. Competition between city-states encouraged innovation and efficiency. The absence of centralized imperial bureaucracy reduced overhead costs and allowed faster adaptation to changing circumstances. City-states could respond to local conditions without waiting for distant imperial authorities.

Cline’s analysis shows how the city-state system enhanced Phoenician resilience during crises. When the Assyrian Empire expanded westward in the ninth and eighth centuries BC, some Phoenician cities fell under imperial control while others maintained independence. When certain cities declined due to warfare or political instability, others flourished. This distributed structure meant no single disaster could eliminate Phoenician civilization.

Economic Diversification and Specialized Production

Phoenician economic success rested on diversified production of high-value goods. They became famous for specific products that commanded premium prices throughout the ancient world. Tyrian purple dye, produced from murex shells, became synonymous with luxury and status. Phoenician glass and metalwork were prized for their quality. Cedar timber from Lebanese mountains was essential for construction projects throughout the treeless Mediterranean.

This specialization in high-value goods generated substantial wealth relative to bulk commodity trade. Rather than competing in grain or basic goods markets, Phoenicians focused on products where their expertise created significant value. This strategy allowed relatively small city-states to generate disproportionate economic influence and accumulate substantial resources.

The Phoenician approach balanced specialization with diversification. While individual cities became famous for particular products, the broader Phoenician commercial network offered diverse goods and services. This combination of specialized excellence and portfolio diversification created economic resilience. If demand for one product declined, Phoenicians could shift emphasis to others.

Cultural Identity and Continuity

Despite geographical dispersion and cultural adaptation in various colonies, Phoenicians maintained strong cultural identity. Shared language, religious practices, commercial networks, and technological knowledge united Phoenician settlements across vast distances. This cultural continuity provided cohesion for decentralized political structures.

Religious practices played particularly important roles in maintaining Phoenician identity. Deities like Baal, Astarte, and Melqart were worshipped throughout Phoenician settlements, providing shared cultural reference points. Religious festivals and rituals reinforced connections between distant communities. When Carthaginian envoys visited Tyre, they reinforced ties through shared religious observances and recognition of Tyre as their mother city.

Phoenician self-identity wasn’t rigid or exclusionary. They maintained core cultural elements while incorporating influences from societies they encountered. This balance between continuity and adaptation proved crucial for long-term success. Rigid cultural conservatism would have limited their ability to operate effectively in diverse contexts, while complete assimilation would have dissolved the networks that made Phoenician commerce valuable.

Lessons from Phoenician Transformation

The Phoenician experience offers valuable lessons about successful adaptation to catastrophic change. First, they recognized that restoration of previous conditions wasn’t possible or desirable. Rather than attempting to recreate Bronze Age territorial kingdoms, they embraced new opportunities created by the collapsed old order. This willingness to fundamentally transform their societal model enabled success where attempts at restoration would have failed.

Second, Phoenicians leveraged existing strengths while developing new capabilities. Their Bronze Age commercial experience provided foundation for expanded maritime trade. Their coastal geography, previously secondary to territorial ambitions, became primary asset. Successful transformation doesn’t require abandoning all previous elements—it involves reconfiguring existing resources toward new objectives.

Third, decentralized networks proved more resilient than centralized structures. The Phoenician city-state system, connected through commercial and cultural networks rather than imperial administration, could absorb shocks that would have destroyed unified empires. This principle remains relevant for modern organizations and societies considering optimal structures for resilience.

Fourth, innovation in communication and organizational technology enabled new forms of social organization. The alphabet facilitated commercial networks that couldn’t have functioned with complex Bronze Age writing systems. Technological innovation, particularly in enabling technologies like communication systems, can create possibilities for entirely new societal forms.

Phoenician Legacy

Phoenician influence on subsequent civilizations proves the durability of their innovations and adaptations. Their alphabet evolved into Greek and Latin scripts that underpin modern Western writing systems. Their maritime technology and commercial practices influenced Greek, Roman, and eventually modern commercial cultures. Carthage, their most successful colony, became a major Mediterranean power that nearly defeated Rome in the Punic Wars.

The term “Phoenician” itself comes from Greek, meaning “purple people” in reference to their famous dye. This external naming reflects how surrounding societies recognized Phoenicians primarily through their commercial activities and specialized products rather than territorial power or military conquests. This legacy differs markedly from empires like Assyria or Egypt, remembered primarily for military achievements and monumental architecture.

Cline’s research in “After 1177 B.C.” emphasizes how Phoenician success contradicts traditional narratives of ancient power. They achieved lasting influence without large territorial empires, prevailed through commerce rather than conquest, and maintained decentralized organization rather than centralized bureaucracy. Their story demonstrates that power and influence can emerge from sources beyond military might and territorial control.

Modern Parallels

The Phoenician transformation resonates with modern challenges and opportunities. In today’s rapidly changing global economy, success increasingly belongs to adaptable organizations and societies rather than those attempting to preserve traditional structures. The Phoenician lesson—that fundamental transformation can be more successful than attempted restoration—applies to communities, industries, and nations facing disruptive change.

Phoenician emphasis on networks rather than hierarchies parallels contemporary trends toward networked organizations and distributed systems. Their demonstration that decentralized structures can prove more resilient than centralized ones offers guidance for designing modern institutions. The Phoenician example shows how smaller, more flexible entities can sometimes outperform larger, more rigid ones when circumstances change rapidly.

Conclusion

The Phoenicians exemplify successful civilizational transformation in the face of catastrophic change. When the Bronze Age world collapsed, they didn’t attempt restoration of lost conditions but instead recognized new opportunities and embraced fundamental transformation. Their pivot toward maritime commerce, development of commercial networks, innovation in communication technology, and maintenance of flexible yet cohesive cultural identity enabled them to not merely survive but thrive for centuries.

Eric H. Cline’s “After 1177 B.C.: The Survival of Civilizations” reveals the Phoenician achievement as one of history’s great success stories in adaptation and resilience. Their experience demonstrates that catastrophic collapse can create opportunities for those willing to embrace change. The Phoenicians teach us that survival during crises often requires transformation rather than restoration, innovation rather than tradition, and flexibility rather than rigidity. These lessons remain powerfully relevant as modern societies navigate their own transformative challenges and opportunities.